Roger Thomas, Bristol North Socialist Party

Fifty years ago, on 4 February 1971, the flagship British engineering company Rolls-Royce collapsed into receivership placing 80,000 workers’ jobs at risk. Workers were informed of the collapse over the Tannoy system while at their benches or desks.

The response of one trade union shop steward expressed the shock and anger: “We are fighting the Battle of Britain all over again”. In parliament, left-wing Labour MP Tony Benn called it a “major national tragedy, a grave blow to confidence in this country”.

Meetings of workers were held at the company’s sites, such as the one in Bristol on 7 February, involving local shop stewards and MPs; and frantic lobbying began to save jobs.

The newly elected Tory government of Prime Minister Edward Heath had made a virtue out of not saving what it called ‘lame duck’ industries, and it had consciously followed a programme of denationalising what it considered fringe assets like Thomas Cook & Son, the travel business, and several hundred pubs.

Too big to fail

But here it was faced with the potential collapse of one of the international powerhouses of British capitalism. Rolls-Royce played a huge role in national and international defence and in civil aviation.

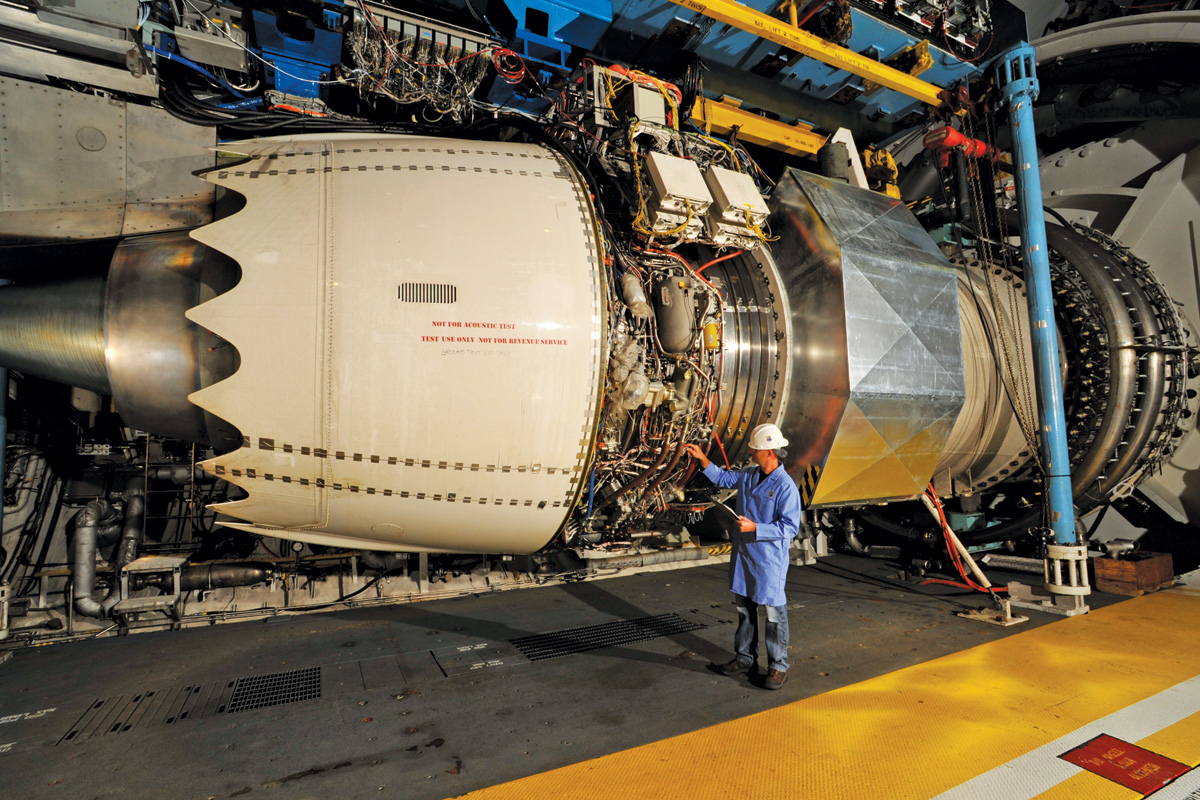

Rolls-Royce had received substantial government assistance over the years, towards development costs. This had especially been the case in respect of the development of a new generation of engines, the RB211.

A cash squeeze developed as engine costs started to outrun the estimates, and the company considered it wise to develop an advanced version of the engine before recouping costs for the original. In 12 months the costs of development had more than doubled.

The Conservative government agreed to a further £42 million in launching aid, with the banks providing a further £18 million as long as the company’s board was restructured with the arrival of Lord Cole, the former head of Unilever, as chair. This money did not arrive as it was contingent on a major audit of the company’s finances.

When this report became public all hell broke loose. Production costs per engine had risen to £460,000 – a loss of £110,000 per engine. The more engines they built, the bigger the loss.

On 22 January the board concluded that the RB211 development could not be met, and on the 26 January decided that, subject to consultations with the government and its main customer the US-based aircraft manufacturer Lockheed, the project should be brought to an end.

On 4 February they brought in the receiver. Trading in Rolls-Royce shares ceased on the London stock exchange, and the FT industrial index dropped 8.7 points, with the stocks of companies heavily linked to Rolls-Royce especially hard hit.

The government held two days of cabinet meetings before announcing that it would step in. Refusing to nationalise Rolls-Royce in its entirety, other sectors, like cars, were left to be disposed of by the receiver.

A government bill to take over Rolls-Royce was prepared and presented to parliament within a week.

Allowing the company to simply collapse was untenable in terms of its effect on the interests of British capitalism in general, and its international standing.

While paying a ‘fair price’ to the shareholders and creditors via the receiver, little concern was expressed in respect of the workers whose jobs were threatened by the arrangements, save that ‘assistance’ would be provided to find new jobs for those made unemployed.

This arrangement also ensured that the government avoided responsibility in respect of commercial liability, whereas full nationalisation of Rolls-Royce would have left them financially exposed.

Nationalisation stabilised the company, which was then privatised by Thatcher in 1987.

The example of 1971 indicates how quickly the ruling class can sanction nationalisation, in this case within days, when its overall interests are threatened. Rolls-Royce was just too important to allow it to go to the wall.

In 1974, faced with mass redundancies by weapons manufacturer Lucas Aerospace, which had large government defence contracts, the combine shop stewards committee appealed to the then Labour government to nationalise the ailing company.

To facilitate this, they drew up a plan of alternative, socially useful production, published in 1976. The Financial Times described it as “one of the most radical alternative plans ever drawn up by workers for their company”. However, it was not implemented because the Wilson/Callaghan Labour government didn’t nationalise Lucas, although industrial action did save some jobs.

New crisis

Rolls-Royce is once again suffering a cash flow crisis arising out of the collapse of air travel in the pandemic, and last year announced 3,000 job cuts in the UK.

However, strike action started in November 2020 by Rolls-Royce workers at the Barnoldswick plant in Lancashire secured a ten-year guarantee for the plant, 350 jobs, and a two-year no compulsory redundancies deal (see ‘Deal secures Rolls-Royce Barnoldswick factory future following strike action’ at socialistparty.org.uk).

During the Covid pandemic, Johnson’s Tory government effectively nationalised the private train operating companies to stop them collapsing after passenger numbers fell precipitously. Also, earlier last year, the probation service – which was partially hived off to for-profit companies, disastrously, in 2014 by minister Chris ‘failing’ Grayling – was renationalised.

These recent examples, along with that of Rolls-Royce in 1971, show that even Tory governments, which are ideologically opposed to nationalised industries and services, can be pressured into making U-turns.

Trade unions worth their salt should not tamely accept closures and widespread redundancies in medium and large-sized companies, but fight to nationalise them.

To secure lasting jobs and good working conditions in the overall economy requires nationalisation under democratic workers’ control and management of the top 125 or so companies, along with the banks, to underpin a socialist plan of production.